The Hartley Colliery Disaster Medal

A part of the Coal Mines Act of 1872 states that no person should be employed in a mine unless there are at least two shafts in communication with each seam being worked; i.e. separate means for both ingress and egress must be employed.

As is the case with most rules and regulations this particular dictate in the Coal Mines Act came about through the bitter lessons learnt through past events, most notably in this case being the catastrophe which befell the New Hartley Colliery in Northumberland on 16 January 1862. For many years prior to this disaster, which even today is unique in mining history, the miners of the Great Northern Coalfield pleaded with the coal owners for greater safety standards. Paramount in their requests was the prohibition of single shaft mines. However, it took the loss of 204 men and boys to provide the impetus for the government and coal owners to introduce such legislation.

Records of coal mining in the Hartley area commence as early as 1291. The original or Old Hartley Colliery was a very successful operation, but was beset by flooding. Over the years this problem had led to a number of miners being drowned despite the fact that from as early as 1760 the mine had employed firstly atmospheric type and then true steam pumping engines to dewater its workings.

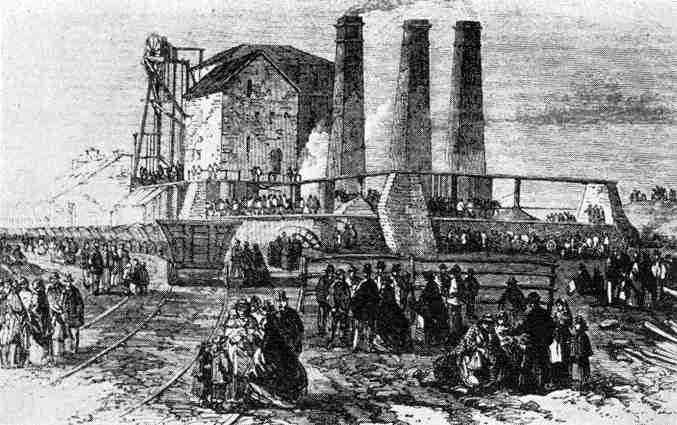

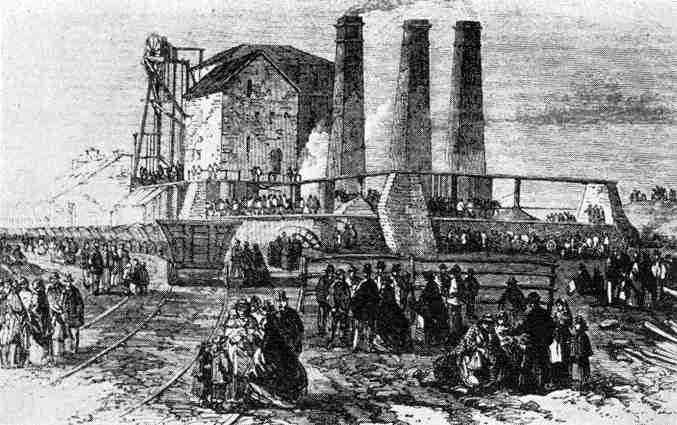

A sketch showing crowds waiting for news of the rescue attempts at Hartley Colliery 1862.

The original Hartley pit was finally inundated from the sea and was closed in 1844. However, such was the profit from coal that a new undertaking was commenced the following year and was named the New Hartley Colliery, better known locally as the "Hester Pit". Messrs. Jobling, Carr & Co., the operators of the new pit, employed William Coulson the master sinker of Durham City to supervise the shaft sinking of their ill-fated colliery. In order to cut the cost of winning the new pit only one shaft was sunk. As was a common practice at that time the Hester Pitís shaft was partitioned for mine ventilation purposes. The up cast half of the shaft contained the pumping rods and apparatus while the down cast side was used for raising and lowering men and coal.

The lowest coal seam in the Hester Pit, the Low Main, was reached on the 29 May 1846. There after the workings were extended towards the East Coast to reach richer coal measures. As had been the case in the Old Hartley Pit flooding plagued the new colliery and on one occasion the entire workforce had to be drawn to the surface when large feeders of water were encountered. The volume of in rushing water was so great that it reached 420 feet up the shaft. To overcome this temporary setback a 300 horsepower beam engine was installed to pump the water in three stages from the bottom of the 600 feet deep shaft. The forty-two ton cast iron beam of the pump was pivoted above the mouth of the shaft and was capable of raising over 1,500 gallons of mine water per minute. This made it by far the largest capacity pumping engine in the north of England.

At 10.30 a.m. on 16 January 1862 the back shift at New Hartley Colliery were in the process of relieving the fore shift which had started at 2.30 a.m. As was the practice at that time one shift relieved the preceding one at the coal face. The first set of eight miners had started to ascend to the surface but of these men only three were to eventually see the light of day. As the cage was rising between the High Main and the Yard seams it suddenly came to a violent halt. Without any warning the beam of the giant pumping engine at the pit top suddenly fractured and twenty-one tons of cast iron hurtled down the shaft taking with it shaft supports, pipes and the ventilation partition. The debris crashed on top of the cage severing two of its four support chains and flinging a number of miners to their deaths while the remainder miraculously clung to the damaged cage. A blockage 30 yards deep then formed at a vital part of the shaft allowing no means of escape for the trapped miners below.

Clinging to the mangled cage was Thomas Watson who was to become the first hero of many in this terrible disaster. Watson was a man of deep religious principles, his testimony at the Coroner's Inquest was that of an eye witness. After gathering his thoughts on that Thursday morning he found himself clinging to the cage, he tried to light a candle with the help of a comrade but this was quickly extinguished by falling water. He then tried to climb up the sides of the shaft, but decided against this on hearing the cries of his comrades below. Climbing down 60 feet below the cage, he tried to give comfort to two fatally injured miners who had been flung from the cage onto the blockage in the shaft below. Due to his perilous situation he rested for a short time then started to climb back up the shaft, suddenly there was a bright unearthly light and from this Watson saw a small recess into which he climbed, exhausted. There he waited twelve hours before he and his remaining comrades in the mangled cage were raised to safety.

Initially Mr. John Short, the colliery enginewright, raised the alarm on the pit top. He then went on to take charge of the initial rescue attempts. By use of a pumping staple the initial rescue party made their way into the High Main seam, from where ropes were dropped down to rescue the men trapped in the cage below. By the end of the first day the damaged cage had been removed and planking placed across the shaft to enable rescuers to be raised and lowered. By Friday the enormity of the disaster was realised, and it was decided to seek the services of the locally renowned mining engineer William Coulson who readily volunteered, bringing with him a number of highly qualified sinkers.

Heroes of the rescue attempt - William Coulson (left) & Thomas Watson (right).

A large number of persons had gathered at the pit head, wives and relatives seeking news of their loved ones, miners anxious to render assistance together with several doctors plus the press. Their wait was to be a long one, hope eventually giving way to despair as the days went by. On Saturday work was progressing steadily but was hampered by falling water and insecure shaft supports. It was then decided to spend time shoring these up. The diameter of the shaft allowed only two rescuers to work at any one time. This they did in shifts working from a plank which was lowered into the shaft. The rescuers toiled in wet and highly dangerous conditions using only candles to illuminate their surroundings. They were in continuous danger from falling stones and water. Their efforts were concentrated on reaching a now buried emergency trap door which had been used for pump maintenance and which provided a direct link into the Yard Seam in which the miners below were trapped. Both the rescuers and the entombed miners knew of the existence of this trap door. By the Monday of the rescue attempt Coulsonís men had cleared the trap door but unfortunately they were driven back by the escape of a large volume of gas that had collected in the sealed workings below.

The rescue attempt had to be abandoned until an adequate supply of fresh air could be brought to the point of rescue. This took a further two days. By about midday on Wednesday a small entrance was forced through the trap door, but again Coulsonís men were, forced back by gas. Eventually this cleared and the rescuers moved cautiously into the maintenance tunnel below the trap door where they found tools which suggested that the trapped men had tried to break out from below the blockage. As the rescuers explored further into the mine workings they began to find the bodies of the gassed miners. The full horror of the disaster was now realised, all men below the blockage had perished. Gas was still hampering progress and the removal of the bodies was postponed until safety could be improved, this included ventilation, road supports and pumping. On the following Saturday the recovery of the bodies began. Due to the restrictions still present in the shaft it took seventeen hours to bring them all to the surface.

In recognition of the gallant actions undertaken by the various rescuers present at the Hartley disaster a special fund was set up to reward them. Donations were given from all over the country including one of £300 from the Relief Committee which had been set up immediately after the disaster to look after the bereaved families. The final presentation to the rescuers took the form of commemorative medals struck in silver and bronze plus one in gold. The award ceremony took place at a grand civic reception held in Newcastle Town Hall on the 20 May 1862 and was specifically held in honour of Coulson and his expert team of sinkers. The Presentation Committee had set aside a fund of £1,587 for the awards. This covered the cost of the medals with the remaining balance of the funds being divided up amongst the rescuers depending on the amount of time each of them had cumulatively spent in the shaft. The medals were commissioned from Mr. Wyon the renowned die sinker and medallist who was then resident at the Royal Mint. Unfortunately the medals were not ready in time for the civic presentation and cardboard replicas had to be presented in lieu.

The

New Hartley Rescue Medal - The edge of this silver medal bears the name of Richard Johnson.According to a report in the "Newcastle Courant" dated 23 May 1862, those rescuers listed below were honoured at the civic reception held in Newcastle. In addition to the various monetary payments handed out each of these men were awarded silver rescue medals, with the exception of their leader, William Coulson, who was given the one and only gold medal produced.

|

Name |

Payment |

Name |

Payment |

|

William Coulson |

Not Stated |

Ralph Heron |

£19 |

|

William Coulson Jnr. |

Not Stated |

Lashley Hope |

£13 |

|

George Emmerson |

£30 |

William Johnson |

£7 |

|

William Shield |

£30 |

Richard Johnson |

£17 |

|

David Wilkinson |

£30 |

Peter Lindsay |

£14 |

|

John Angus |

£8 |

John Little |

£17 |

|

John Burns |

£14 |

R. Maughan |

£16 |

|

Mitchell Bailey |

£6 |

John Manderson |

£11 |

|

Fenwick Charlton |

£6 |

Robert Milburne |

£5 |

|

Matthew Chapman |

£14 |

James Mutters |

£14 |

|

Edward Davison |

£15 |

John Nevis |

£4 |

|

Matthew Dobbs |

£16 |

George Pace |

£11 |

|

George Graham |

£8 |

William Reed |

£19 |

|

John Henderson |

£10 |

John Smith |

£17 |

|

Thomas Hetherington |

£6 |

Henry Snowden |

£17 |

|

Ralph Harrison |

£14 |

John Sedgwick |

£13 |

|

Robert Hamilton |

£4 |

Andrew Swaine |

£19 |

|

John Heron |

£18 |

Jesse Smith |

£5 |

|

Elsdon Heron |

£19 |

Robert Wilson |

£16 |

It is not known how many bronze rescue medals were produced or to whom and when they were issued. It is most probable that they were presented to those in the initial rescue party organised by John Short and to those who were later engaged in searching the workings for survivors and finally in the grizzly retrieval of the bodies.

The New Hartley Rescue Medal -

Bronze variety.It appears that all of the medals were struck from the same die and were 52 mm in diameter. However, only the silver and presumably the one gold medal were engraved along their edges with the names of their respective recipients. The latter medals were also joined via a crimp type attachment onto a suspension bar that in turn allowed them to be worn on a crimson ribbon the approximate dimensions of which were 50mm wide by 75mm long. A general description of the design of the Hartley Disaster Medal is given below;

Obverse: An allegorical scene depicting two miners with pick and shovel working to free the bodies of two trapped comrades under a fall of rock. On the left a winged figure with a sword appears to be guiding the activities of the rescuers. The makers signature "J.S. & A.B. WYON SC." appears in minute legend along the outer left edge of the die design.

Reverse: A legend arranged in three panels between sprays of oak leaves reads; Top panel PRESENTED TO THOSE; Centre panel WHO RISKED THEIR / OWN LIVES IN ATTEMPTING / TO SAVE THE LIVES OF THEIR / FELLOW WORKMEN BURIED / IN HARTLEY COLLIERY; Bottom panel JANUARY 1862.

Several days after the disaster at New Hartley Colliery a large meeting of miners from pits throughout the area, was held at Newcastle. A petition was drawn up demanding that two shafts to every pit be made compulsory by law. As a direct result an Act was passed to that effect, later that same year.

Immediately after the disaster New Hartley Colliery was closed and its royalty remained untouched. However, by 1874 the lure of those riches still wrapped up in the untouched portion of the mineís reserves prompted the royaltyís new operators, Seaton Delaval Collieries Ltd., to sink a new mine, close by the location previously occupied by the old Hester Pit. The shafts of the new mine were named the Hastings and Melton Pits in an attempt to disassociate the new winning with the name of its ill-fated predecessor. Despite this the name of New Hartley persisted and within a few years the pit became known as the New Hartley Hastings Colliery. Although this new mine didnít go as far as re-opening the now capped and still partially blocked shaft of the old Hester Pit it did drain and eventually allow a break into the original Low Main workings of New Hartley. What a ghostly picture must have confronted those colliers in 1900 as they re-entered the wet, dank and foisty world of that most infamous of British collieries;

"The scene then presented was a strange and weird one. In many parts of the workings the tubs and gear were found standing ready as if for the resumption of the work which was so hurriedly abandoned more than 38 years previously."

T.E. Foster.

Footnote:

Two Pre 1943 lamp/cage riding checks issued in the name of Hartley Main Collieries Ltd. (HMC) plus an earlier pre 1929 lamp issuing check for the New Hartley Hastings Pit of the Seaton Delaval Coal Company Ltd. (i.e. S.D.C.C.).

New Hartley Hastings Colliery continued to operate well into the twentieth century. In 1929 Seaton Delaval Collieries amalgamated with the Cramlington Coal Company to form Hartley Main Collieries Ltd. This heralded the start of a major reconstruction of the colliery that included a great deal of modernisation and re-investment into its future within the new group. In 1943 Hartley Main Collieries Ltd. was taken over by the Bedlington Coal Company Ltd. The mineís new operators made little changes to the New Hartley operations so by the time the pit was nationalised in 1947 the National Coal Board inherited a fairly modern and well run production unit. However, once under the control of the N.C.B. the pitís production began to fall and it was allowed to stagnate. This was despite the colliery having estimated reserves in its lower measures to last a further 70 years at its peak production level of 200,000 tons per annum. The colliery finally closed in February 1959 bringing to an end nearly 700 years of coal mining history in the Hartley area of Northumberland.

References:

1) The Hartley Colliery Disaster. J.E. McCutcheon. 1963.

2) Memoirs of the Hartley Colliery Accident and Relief Fund. T.E. Forster. 1912.

3) The Collieries of Northumberland. Volume II. J.T. Tuck.

Further Reading:

The following web sites will be of interest to those who are seeking further history relating to the New Hartley Disaster.

The New Hartley Colliery Disaster of 1862 - A list of those killed in the disaster plus family history details of those bereaved families.

Hartley Colliery Disaster Memorial - A collection of images of the disaster memorial in Earsdon Churchyard, Northumberland.

Adapted from an original article by Jeff Gardiner first published in the Seaby Coin and Medal Bulletin, March 1983. © Jeff Gardiner & Mark Smith 2001.